Chapter 6: The US Electric Grid in Peril

- Sean M. Walsh

- Dec 13, 2025

- 11 min read

Updated: Jan 22

America's electric grid is largely past its expiration date and effectively incapable of meaningful expansion.

"I'm givin' it all she's got... she can't take much morrrre, Captain!" -Scotty, USS Enterprise

Key Points:

1. Much of the US electric grid is very old, up to 100 years old, so old in fact that significant components are many decades beyond their intended design life.

2. Because of the centralized design of the US electric grid, even tiny part failures cause financial, human, and environmental disasters.

3. Because of the grid’s age and $trillions of accumulated deferred maintenance, these catastrophic electric grid failures are increasing every year.

4. The grid has effectively lost its ability to expand — transmission projects now face 5-7 year delays, transformer lead times exceed 4 years, and the US needs 500,000 more electricians just to maintain current infrastructure.

5. The aging US grid is failing faster than it can be repaired. Combined with near gridlock to expansion , the US grid cannot possibly meet the 44+ GW of new AI datacenter electricity demand by 2028.

6. Alternative solutions must be used if this massive electricity shortage is to be filled.

Key Stats:

$16.65 Billion - estimated total cost of the PG&E transmission line failure that caused the "Camp Fire" in 2018.

22 cents - original cost of the failed c-hook, installed in 1918, which caused the Camp Fire disaster, bankrupting one of America's largest electricity companies, PG&E.

50 years - number of years past its design life, the Camp Fire c-hook was when it finally broke (at about 100 years old!).

153,336 acres - total area burned by the PG&E Camp Fire disaster.

500,000 miles - estimated total length of transmission lines in the US electric grid.

2,500,000 - estimated number of hooks supporting cables in the US electric grid.

104,000 Megawatts - total amount of planned electric generation plant retirement by 2030 (expected to increase outage risk by 100x).

20% - 104,000MW of electricity generation is about 20% of total US capacity.

40 years - average age of substation transformers in the US electric grid, which typically have a design life of 25-30 years.

The 22 Cent Hook That Incinerated Paradise, and Bankrupted One of America's Largest Electric Companies

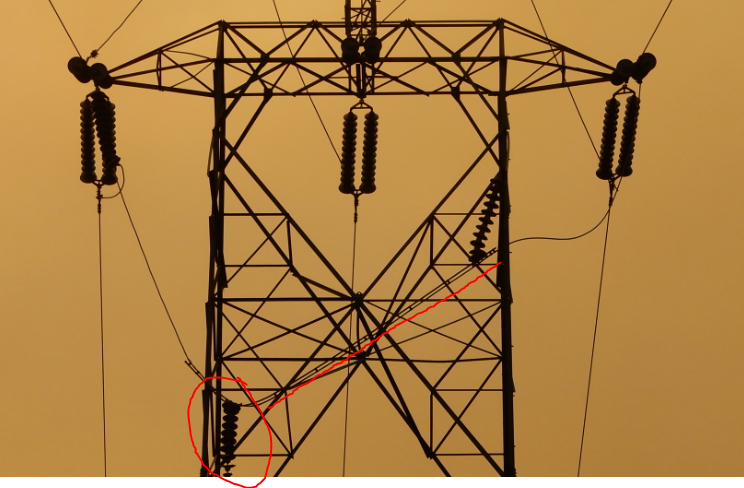

A 100-year-old Pacific Gas & Electric C-Hook finally broke...

It caused the transmission cable it was supporting to short-out...

Instantly sending molten aluminum of over 5,000 degrees F showering onto dry brush below...

The fire burned over 150,000 acres...

And incinerated 18,000 homes and buildings, in Paradise, California...

And, PG&E, one of America's largest electric companies, filed for bankruptcy claiming disaster-related liabilities of up to $30 billion...

November 8, 2018. 6:15 a.m. Pulga, Butte County, California.

In the Feather River Canyon, a California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection captain arrived above PG&E's Poe Dam just before sunrise. What he witnessed sent a chill through him: the beginnings of a conflagration under a high-voltage power line on the ridge top across the river. The fire was already exploding toward the south and west, riding the notorious Jarbo Winds, which were so fierce the captain struggled to remain upright.

He radioed headquarters with urgency in his voice. His crew would never get in front of this fire. "This has the potential of a major incident," he told dispatchers—a prophetic understatement.

Within hours, Cal Fire investigators traced the ignition point to Tower #27/222 on PG&E's Caribou-Palermo 115 kV transmission line. A single metal suspension hook—known as a "C-hook"—had failed. When it broke, a live cable fell and struck the steel tower, arcing at temperatures between 5,000 and 10,000 degrees Fahrenheit. Sparks showered into the dry vegetation below.

In less than an hour, the fire had torn through Pulga and the mountain hamlet of Concow and reached the eastern outskirts of Paradise. The town of 26,000 people was hit from three sides by massive walls of fire. In a matter of hours, it was utterly destroyed.

The Camp Fire burned 153,336 acres. It destroyed more than 18,000 structures, including nearly 13,700 single-family residences. Eighty-five people died—the deadliest wildfire in California history. Conservative estimates put total damage at $16.65 billion.

All from one 22 cent hook.

When Butte County District Attorney Michael Ramsey announced the results of his 18-month investigation, he revealed the devastating details. The C-hook had been purchased by Great Western Power Company in 1919 for 22 cents. PG&E acquired the transmission line in 1930 and never replaced the hook. For nearly a century, it hung in the windy environs of the Feather River Canyon, wearing down unchecked.

Its design life was 50 years. It was 97 years old when it broke.

"It broke," Ramsey said simply. "And that is what killed 85 citizens."

PG&E pleaded guilty to 85 counts of involuntary manslaughter—the first time in U.S. history a company was charged and found guilty of homicide. The company's "run to failure" maintenance policy—replacing parts only after they failed—had elevated negligence to a crime.

This wasn't an isolated incident. It was a symptom of two interconnected problems that threaten the entire American electric grid.

The Two Problems

The American electric grid faces a crisis that can be understood in two parts.

Problem One: A vast amount of grid infrastructure is decades beyond its design life, in desperate need of replacement.

Problem Two: The US electric grid has lost its ability to expand, grinding to a near halt.

Both problems are accelerating simultaneously. Together, they make it mathematically impossible for the grid to meet exploding AI electricity demand—the 44-47 GW shortfall we explored in previous chapters.

The Camp Fire hook wasn't an anomaly. It was a preview of what happens when infrastructure exceeds its expiration date by decades. And we have millions of similar components scattered across 500,000 miles of transmission lines, 75,000 substations, and tens of millions of transformers.

Understanding these twin crises is essential to understanding why any solution that depends on the grid is no solution at all.

Problem 1: Grid Infrastructure On Borrowed Time

The heart of America's electric grid is its fleet of transformers—the devices that step voltage up for long-distance transmission and back down for distribution to homes and businesses. Without them, the grid simply cannot function.

The numbers are overwhelming.

According to industry analyses, the United States has between 60 and 80 million high-voltage distribution transformers in service. Approximately 55% of residential distribution transformers are nearing or have exceeded their typical design life of 30-40 years. Many units have been running for 40 years or longer.

The Department of Energy has reported that large power transformers are "typically considered to have a design lifetime on the order of 40 years," but the average age of large power transformers in the North American grid is already 38-40 years. This indicates that "a substantial fraction of those LPTs are at or over that design lifetime" and "will ultimately need to be replaced or refurbished."

According to DOE data, 70 percent of transmission lines are over 25 years old and "approaching the end of their typical 50–80-year lifecycle." Most were built during the 1950s and 1960s, designed for a 50-year service life. They're now well past expiration.

The 75,000 substations operated by more than 3,000 utilities across the country face similar aging issues. A single substation failure can black out thousands to millions of people. Broader regional blackouts cost billions per occurrence.

The consequences are already visible. From 2015 to 2020, annual US blackouts doubled. This isn't coincidence—it's the predictable result of infrastructure exceeding its design life on a massive scale.

The Camp Fire hook is one data point in an ocean of deferred maintenance. The California Public Utilities Commission's investigation found that PG&E's lapses "were not isolated, but rather indicative of an overall pattern of inadequate inspection and maintenance of PG&E's transmission facilities."

That pattern extends far beyond one utility or one state. It's a national emergency.

Problem 2: The Grid Probably Can't Expand

Even if we could wave a magic wand and replace every aging component tomorrow, the grid faces an equally severe constraint: it has largely lost its ability to expand.

More overwhelming evidence.

Interconnection backlogs have exploded. According to Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, nearly 2,600 gigawatts of generation and storage capacity are now actively seeking grid interconnection—more than twice the total installed capacity of the existing U.S. power plant fleet. The backlog increased nearly eightfold over the last decade.

Median time from interconnection request to commercial operation now averages about five years, up from under two years a decade ago. Historical data show only 19% of projects entering U.S. queues between 2000-2018 have reached commercial operation. The vast majority are cancelled, withdrawn, or still waiting.

Supply chains have collapsed. The North American Electric Reliability Corporation reports that lead times for standard transformers hit roughly 120 weeks (more than two years) in 2024, with large power transformers taking as long as 210 weeks—up to four years. Circuit breakers now take 151 weeks (nearly three years), double pre-pandemic norms.

Prices have increased 60-80% since 2020. According to the International Energy Agency, transformer prices rose approximately 75% compared to 2019 levels.

The situation extends beyond transformers. Siemens Energy recently reported a record $158 billion backlog for natural gas turbines, with some turbine frames sold out for as long as seven years. High-voltage direct-current cables now take more than 24 months to procure, with some undersea cable orders taking more than a decade to fill.

Labor shortages compound every problem. The electrical workforce is projected to shrink by 14% by 2030, while demand could increase by as much as 25% over the same period. According to Microsoft's analysis, the U.S. needs to recruit and train approximately 500,000 new electricians over the next decade—200,000 to replace retiring workers and 300,000 to meet growing demand.

The paradox is stark: spending on transmission is higher than ever, but fewer new miles are being built. Money alone cannot solve timeline problems. You cannot write a check that compresses a 15-year permitting process into 15 months, or conjures transformers that take four years to manufacture.

From CleanerEnergyGrid.org...

Construction of new high-voltage transmission lines has continued to slow. Transmission spending hit an all-time high in 2023, but the U.S. only builds 20% as much new transmission in the 2020s as it did in the first half of the 2010s. This trend began over a decade ago, when the average of 1,700 miles of new high-voltage transmission built per year from 2010 to 2014 dropped to only 925 miles from 2015 to 2019, and has fallen further to an average of 350 miles per year from 2020 to 2023. Only 55 new miles of high-voltage transmission were constructed in 2023.

The Power Plant Retirement Crisis

As if aging infrastructure and expansion gridlock weren't enough, the supply side is actually shrinking.

In July 2025, the Department of Energy released its Report on Evaluating U.S. Grid Reliability and Security. The findings are sobering.

The analysis reveals that 104 GW of firm generation is scheduled to retire by 2030. These are coal plants, natural gas facilities, and other "baseload" sources that provide reliable, around-the-clock power regardless of weather conditions.

What's replacing them? The report found that 209 GW of new generation is planned by 2030—but only 22 GW comes from firm baseload sources. The rest is primarily wind and solar, which depend on weather conditions and cannot provide the same reliability profile.

The gap: 82 GW of firm capacity disappearing, with no equivalent replacement.

The consequences are severe. According to the DOE, "allowing 104 GW of firm generation to retire by 2030—without timely replacement—could lead to significant outages when weather conditions do not accommodate wind and solar generation."

How significant? The modeling shows annual outage hours could increase from single digits today to more than 800 hours per year—a 100-fold increase. Even assuming no additional retirements beyond current schedules, outage risk in several regions rises more than 30-fold.

The math is unforgiving. We're subtracting firm capacity faster than we're adding it, while simultaneously facing unprecedented demand growth from AI and electrification.

AI Demand Growing, Electricity Supply Shrinking... A Collision Course

Now connect these grid realities to the AI infrastructure crisis we've explored in previous chapters.

The picture is devastating.

Morgan Stanley's analysis identified a 44-47 GW shortfall for AI datacenters by 2028. Data center electricity demand projections reach 300-400 TWh per year by 2030—equivalent to 53-71% of Texas's entire 2024 electricity generation. The U.S. would require 90% of global semiconductor manufacturing output just to support announced datacenter load.

Power constraints are already extending datacenter construction timelines by 24-72 months. In Santa Clara, as we noted in earlier chapters, 100 MW of new datacenter capacity sits dark—the buildings are complete, the equipment is installed, but there's no power to run them.

The National Renewable Energy Laboratory estimates the U.S. may need twice as many transformers as currently exist to support projected demand growth. But transformers take 4+ years to procure. And the ones we have are already past their expiration date.

The collision course is mathematically certain:

Demand: 69 GW of new AI datacenter load needed by 2028, growing to 100+ GW by decade's end.

Supply constraints: 104 GW of firm generation retiring by 2030, replaced by only 22 GW of firm capacity.

Infrastructure: 20+ million transformers past design life, 4+ year lead times for replacements.

Expansion: 5-7 year interconnection delays, 500,000 electrician shortage.

These numbers simply don't reconcile. The grid cannot meet this demand. Not in the required timeframe. Not with the existing infrastructure. Not with the supply chains that exist today.

An Inescapable Conclusion

I've spent the last several chapters building to this point, and now I'll state it plainly.

The American electric grid cannot be fixed fast enough to meet AI infrastructure demands.

It cannot be expanded fast enough. The interconnection queues stretch years into the future, and no amount of money can compress the physics of permitting, construction, and commissioning.

It is retiring firm capacity faster than it's adding it. The 82 GW gap between retirements and replacements will make reliability worse, not better.

Its existing infrastructure is failing faster than it can be replaced. When a 97-year-old hook can cause $16.65 billion in damage and 85 deaths, and there are millions of similar components throughout the system, the risk profile is unacceptable.

Therefore: Any solution that depends on the grid is not a solution at all.

For AI companies planning infrastructure buildouts, for investors evaluating data center opportunities, for policymakers trying to ensure American technological leadership—the conclusion is unavoidable. The grid cannot be the foundation for the next decade of computing infrastructure.

Off-grid systems appear to by the only viable path for meeting the timeline and scale requirements of modern AI development.

In coming chapters, I will detail what I believe to be the most elegant, practical, and profitable solution to this crisis: Solar Computing Clusters.

These are fully off-grid, energy-independent data centers that sidestep every bottleneck we've discussed:

They sidestep interconnection queues — no grid connection needed, no waiting in line for approval

They sidestep transformer shortages — self-contained power generation and storage, no reliance on utility infrastructure.

They sidestep aging infrastructure — purpose-built, modern systems with known reliability profiles.

They can be deployed in 12-18 months, not 5-7 years — capturing billions in revenue that would otherwise be lost waiting.

I've spent more than five years developing this technology. I've built commercial-scale prototypes. I've proven the concept works.

While the legacy industry waits in queues, negotiates for grid connections, and hopes another 100-year-old hook costing 22 cents doesn't fail, there's an immeasurably better path.

The legacy electricity industry served its purpose for a century. But it cannot be the fastest-growing consumer in the next one. It cannot serve AI computing.

Learn more about my work at www.639solar.com.

Sources:

2018 Camp Fire Tweet Thread, TubeTimeUS

Supply Chain Delays Push Power Grid, Fast Company

Utilities: Last Week Tonight, John Oliver

Examining How A PG&E Transmission Line Claimed 85 Lives, Hackaday

Report Evaluating US Grid Reliability And Security, Us Department Of Energy

The US Is Headed For A Power Grid Crisis, Forbes

Electrical Utility Substations The Grid's Most Pressured Link, Trystar

Power Plants Seeking Transmission Interconnection, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory

Queued Up: 2024 Edition, Berkeley Lab

PG&E Files for Bankruptcy, NPR

Transmission Interconnection Roadmap, US Department Of Energy

Explainer on The Interconnection Final Rule, Federal Energy Regulatory Commission

Fewer New Miles, CleanEnergyGrid

Can US Infrastructure Keep Up With the AI Economy?, Deloitte

9 Of the Worst Power Outages in US History, ElectricChoice

What Really Happened During the 2003 Blackout?, PracticalEngineering

Hidden Threats in Our Power Grid: the Chinese Transformer Backdoor Scandal, Stu Sjoureman

What Is Driving the Demand for Distribution Transformers?, National Renewable Energy Laboratory

Power Check: Watt's Going on With the Grid?, Bank Of America Institute

PG&Es Road Toward Bankruptcy, CapRadio

California Power Provider PG&E Files for Bankruptcy in Wake of Fire Lawsuits, NPR

The Grid Could be Down for Years if LPTs Destroyed, EnergySkeptic

Interactive Map of US Power Plants, ArcGIS